Bryan Harvey remembers well the moment the “zero” seed—that was pivotal to the development of canola from rapeseed—was identified in one of the hundreds of samples he was analyzing in the National Research Council’s (NRC) Prairie Regional Laboratory (PRL) run by organic chemist Burton Craig.

Harvey was the first University of Saskatchewan (U of S) graduate student in the early 1960s to work with geneticist Keith Downey, then senior research scientist with Agriculture Canada’s research station and an adjunct professor in the U of S College of Agriculture.

Harvey was feeding some samples into a gas-liquid chromatography instrument from a line of rapeseed Downey had screened for lower erucic acid content when Craig, who was standing nearby, noticed a distinctive difference in the fatty acid profile of one sample.

“What is that?” he asked immediately. What the graph signified was that the sample registered zero for erucic acid, when typically rapeseed would register in the range of 40 per cent for the fatty acid. High levels of erucic acid are not considered safe for human consumption.

“Well, Burt got out a big stamp, certified it, signed it, dated it and so on,” Harvey recalls.

Harvey, in collaboration with Agriculture Canada scientists, went on to cross with regular rapeseed the “zero” seeds that had been produced by Liho, a Polish variety used as forage crop for its leafiness, and worked out the inheritance properties of the trait. It was the first step in developing canola, and that seed was the progenitor to the yellow oilseed crop that has become dominant across the prairies.

Harvey and Downey also developed the “half-seed” technique that was vital to the development of canola by allowing the oil in individual seeds to be analyzed without having to destroy them.

The technique involved using a delicate scalpel and forceps designed for eye surgery. They would use the instruments to remove the seed coat from a rapeseed kernel and then peel off a single cotyledon to analyze it for erucic acid content, leaving the remaining second cotyledon and attached shoot free to germinate. The method is still used by plant breeders 50 years later.

Harvey explains that their success had much to do with the highly sensitive gas-liquid chromatograph developed by Craig and NRC technologist Martin Mallard, which reduced the required seed sample from about half a kilogram to essentially half a seed.

The next step in plant breeding to develop a readily consumable oil and feed product from rapeseed required the removal of glucosinolates—an anti-nutritional compound that limited the amount of crushed seeds that can be used as meal to feed animals.

Downey and Baldur Stefansson of the University of Manitoba addressed this challenge by using genes from a Polish variety of rapeseed, Bronowski, led to their recognition as the “fathers of canola.”

In 1974, Stefansson developed the first low erucic acid, low glucosinolate Argentinian rapeseed variety called Tower. By 1977, Downey presented the world’s first “double-low” (low in both erucic acid and glucosinolate) variety of Polish variety rapeseed suited to northern growing areas.

The development of canola from rapeseed, which used to be a relatively minor crop in Saskatchewan, has its origins in the work done by scientists who explored ways to separate the oil into edible and industrial components.

William White, a plant breeder with the Dominion Forage Laboratory of Agriculture Canada, and Hank Sallans, an oilseeds chemist with the NRC, were among a few scientists who in the early 1940s researched rapeseed.

Whether it was the early work done by Les Wetter of the PRL and Milton Bell of the university’s animal husbandry department on the use of rapeseed meal, or the contribution of PRL’s Clare Youngs toward developing a method to heat kill the enzyme myrosinase to avoid the creation of undesirable elements in feed, the foundation for canola was laid over three decades of perseverance and co-operation by scientists from several institutions.

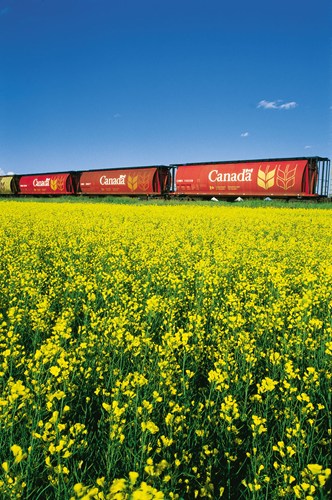

The collective effort of these scientists has transformed a minor crop with limited use (the traditional rapeseed plant had been primarily used as an industrial lubricant) into one of the country’s most valuable crops, one that is used in dozens of products from cooking oil to printing ink.

The U of S remains actively involved in canola research, particularly in the area of using canola meal in livestock nutrition and in biodiesel production from canola oil.

The report by LMC International for the council says canola generates about $26.7 billion in total economic benefits to Canada annually, with 250,000 people working in careers related to the industry.

Sarath Peiris is a communications contributor with U of S Research Profile and Impact