Inspired research, great timing and meeting the diverse needs of the value chain that extends from the farmer to the maltster to the brewer to the beer drinker contributed to making Harrington barley one of the greatest successes to come out of the labs of the University of Saskatchewan.

Developed by geneticist Bryan Harvey at the Crop Development Centre and released in 1981, the variety was named for James B. Harrington, the former head of the field husbandry department and a prolific plant breeder who developed varieties of barley, wheat, oats, flax and rye quickly.

Farmers, maltsters and brewers immediately recognized its potential. The newcomer was superior to popular barley varieties of the day in almost every way; it had higher yields, uniformly sized and plumper kernels that made for easier processing, improved enzyme levels and higher extraction rates (the amount of alcohol produced by the fermentable material). Harrington provided good colour and flavour as well as excellent beer shelf life.

Crucially, Harrington could be turned into malt two days faster than previous varieties that took about six days—a difference that boosted capacity at malting plants by 20 per cent with no additional capital investment. While other barley varieties had a dormancy period that required them to be kept in storage after harvest for up to several months, Harrington could be malted straight from the field.

Even though the highly competitive brewing market is highly conservative, with big companies reluctant to change from proven varieties, Harvey notes that Harrington caught on much faster than is typical for new varieties.

Seed of the Year award organizers chose Harrington in 2009, pegging the value of the more than three billion bushels of the variety produced at more than $15 billion.

Harvey developed Harrington using as parents an American two-row variety called Klages that had good enzymatic activity but wasn’t great for dry weather, as well others such as Betzes and Centennial and a Dutch variety, Zephyr, which was widely adaptive and gave Harrington some of its characteristics. He had input from plant scientist Brian Rossnagel who joined CDC to work on the feed side of barley, and the two went on to be partners in the development of several other varieties including CDC Kendall and CDC Copeland.

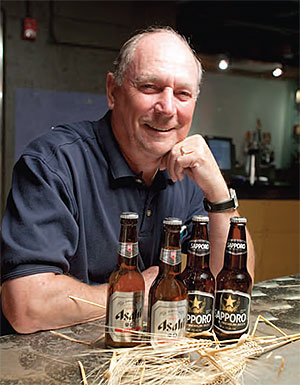

Working with Rossnagel, a team of specialists and companies like the Japanese beer giant Sapporo, Harvey also had to maintain a relationship with the multifaceted beer industry, from the malters and brewers to the agricultural producers themselves, who often have different perspectives on their respective requirements.

As Harvey explains, many factors contributed to the success of Harrington, the first two-row barley developed to meet growing conditions in Western Canada. The North American beer market at the time relied on six-row barley for the high enzymatic activity required for a brewing process that used “adjuncts” (mainly rice or corn) to provide the starch that’s converted to sugar for fermentation.

Given the prairies’ harsh climate with non-optimal temperatures and rainfall, short growing season and distance to port, barley producers needed to compete on quality, not on higher yields.

During the 15-year process it took to develop Harrington, the population and economies in countries such as Japan were growing, creating wealth that could be spent on luxuries such as beer. There was a market for the high enzyme barley ideal for the adjunct -reliant beer making in Japan, China and other countries.

“It hit the market at the right time, where it had a shortage of malting barley of any kind,” Harvey said.

Harrington’s 20-year reign began to wane by the early 2000s, and today has been relegated to the sidelines by varieties such as CDC Copeland—also developed by Harvey—that have higher yields, stronger straw and are more disease resistant.

Sarath Peiris is a communications contributor for U of S Research Profile and Impact.